I have been maintaining hub, the command-line git extension, for 10 years. After 2,100 issues and pull requests closed, 18k+ stars on GitHub, and countless hours invested in it, I thought it might be fitting to reflect on its unlikely past, share a bit about my process working on it, and address the future of GitHub on the command line.

In 2010, the entire implementation of hub 1.0 sat in a single Ruby file of less than 500 lines of code.

Hub was created as a pet project of Chris Wanstrath, the co-founder and then-CEO of GitHub. The initial idea behind hub was simple: use it to wrap git, and hub will expand arguments for you so you can type less while working with GitHub. For example, you can do git clone <owner>/<repo> instead of typing the full URL. In fact, expanding shorthand syntax to full URLs was most of what hub did back then—it didn’t even consult the GitHub API to perform any of its features.

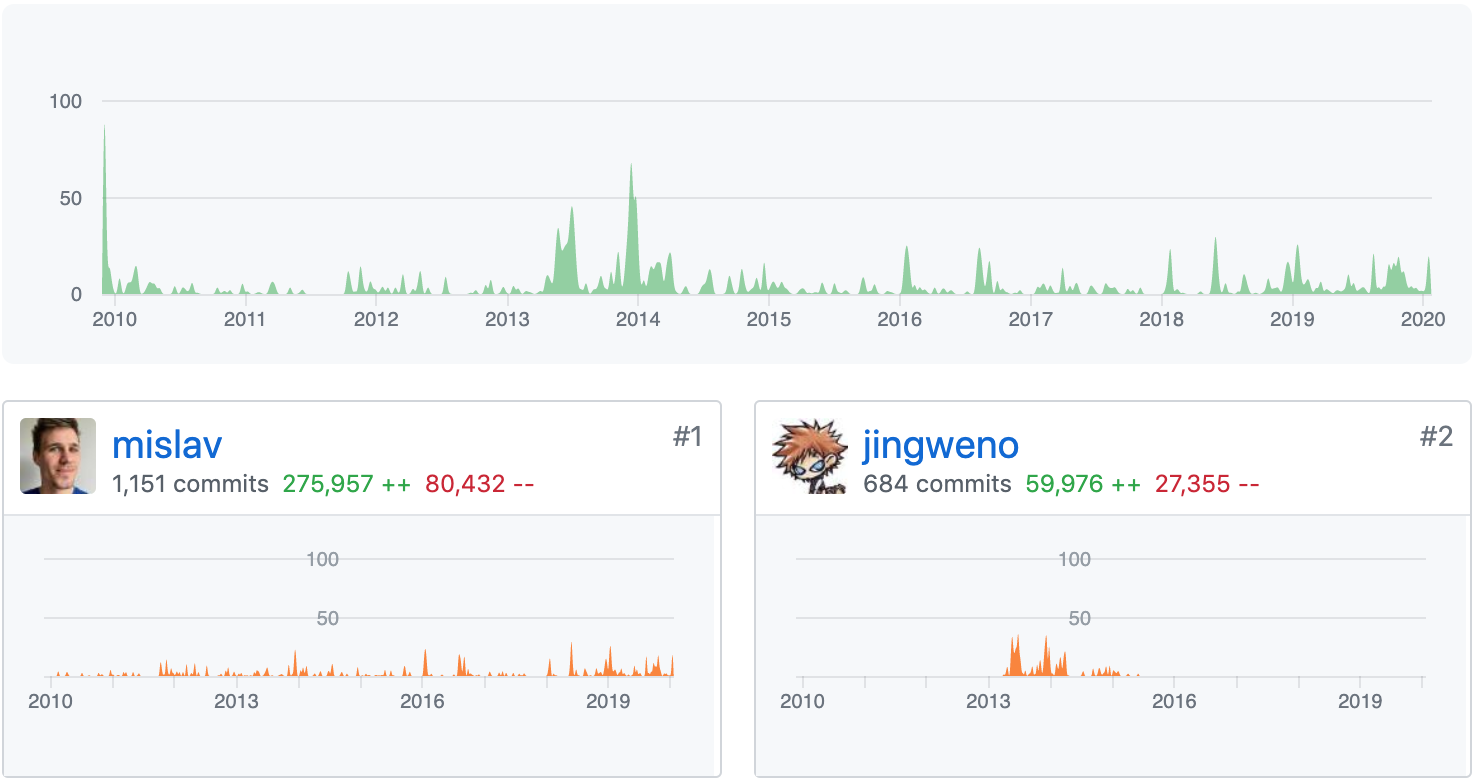

I liked the idea of hub and I started contributing to the project early on. Chris’ own involvement has tapered off over the course of a year and, after a while, I was the only one who decided on hub’s features. In the long run, this might have not been great for the overall health of the project.

Since it is relatively easy to prototype new features in Ruby, I started expanding hub to wrap even more git commands, enabling it to do powerful things that literally nobody has asked for, such as cherry-picking commits from GitHub URLs. At the same time, together with other contributors I have also been adding brand new commands to hub such as create, fork, and pull-request. I did not recognize this at the time, but this went completely against the initial design of hub, which had mostly aimed to wrap existing git commands, and where the only “custom” hub command was browse.

Meanwhile, the original premise of hub being a wrapper for git was disappointing people who have tried it and concluded that it makes git a magnitude slower, sometimes even by more than 140ms. The slowness of hub has prompted Owen Ou (@jingweno) to create his own re-implementation of hub called “gh”, written entirely in an up-and-coming language called Go.

The much faster “gh” has hit a chord with the community. Coincidentally, a couple of GitHubbers were at the time paving the way for Go being used internally for GitHub microservices, and they pitched the idea that GitHub adopts the implementation of “gh” as the official “GitHub CLI”.

The way this unfolded at the time gave me mixed feelings. While I was also really impressed with Owen’s re-implementation, the idea shoving hub’s legacy to the side and promoting a relatively new project into something “official” didn’t sit well with me, primarily because I wasn’t initially included nor consulted in this planing, but also because I was worried about the incompatibilities between the implementations. So, I worked with Owen for over 6 months, teaching myself Go in the process, so that we could get to a point where the new implementation passed the entirety of hub’s test suite. Since I was nomadic at the time, at one point we even met up in Vancouver and sat down to hack on the project together. Making connections like these is what makes me happy about the world of open source.

In October 2014, Owen had the privilege to merge his hard work into the mainline and subsequently delete the entirety of the old Ruby implementation. (It turns out, git supports merging branches even if they have unrelated histories, so we were able to preserve complete histories of both projects in a single repository.) It’s the most epic rewrite that I have ever participated in, and I thank Owen for investing his patience and trust in me, and for making hub better for everyone.

We continued to call the project “hub” and never labeled it “the GitHub CLI”, though. This was because, by then, the limitations and the ensuing identity crisis of hub’s design was becoming apparent to me, and I couldn’t really endorse it as an official product in good faith. Hub continued to live on under the github org, but more as a sandbox where I continued to experiment with the possibilities of using the GitHub API on the command line.

And such a sandbox it was. Over the years, hub accumulated a portfolio of wild hacks that partly served a practical purpose, but that were mostly done to satisfy my thirst for experimentation. Some of these are:

-

To speed up execution back in the Ruby days, hub used to stub parts of the Ruby standard library that have proved to be slow to load. Tricks like these, when combined together, would sometimes result in considerable net gain.

-

Hub generates its own man pages by first converting its help text into Markdown syntax, then converting Markdown into the “roff” format typically consumed by

man. -

Hub uses its own

hub releasecommand to publish new versions of itself during a CI run. -

Most of hub’s test suite is written using BDD-style with Cucumber and still executes with Ruby. In fact, since the test suite consistently invokes

hubas an executable from the “outside” and inspects its output/outcomes, we were able to keep the entire test suite when migrating from Ruby to Go. This largely enabled the rewrite in the first place. -

Because of the way we test hub, using standard Go tooling to generate a code coverage report after a test run is not feasible for us. Hub therefore measures code coverage using a haphazardly put-together workaround.

-

Hub tests its own shell completion scripts using Cucumber as well by spinning up an interactive shell in a terminal emulator internally, sending keystrokes to that terminal, and inspecting the result.

-

To have its command-line flag parsing be as close to git as possible, hub implements its own POSIX-compatible flag parser in about 200 lines of code. It also defines the list of supported flags for each command by scanning that command’s help text.

I think that something that I did right with hub was that I never forgot to have fun while making it. This, combined with my keeping of healthy boundaries when dealing with the users’ requests, has significantly helped me stave off the onset of burnout.

It was clear to me, however, that I won’t be working on this project for the next 10 years as well.

Being my first Go project, hub is spectacularly messy, as it is evident from the existence of such constructs as the “github” package which encapsulates basically half of the entire codebase. Furthermore, as hub was getting more features in the form of new commands, it became to dawn on me that I’m really resisting upholding hub’s original premise of being a git wrapper, and so I stopped suggesting in the documentation that people do alias git=hub in their shells. In fact, I haven’t used it in the aliased form myself for several years already.

Expanding the git command with new features may sound like a fun gimmick, but is in fact surprisingly hard to maintain. Even though git lets you add new custom commands by adding git-<whatever> executables to your PATH, it’s not possible to override git core commands using that mechanism. To augment core commands you would need to create a new program that acts like git and convince people to alias your program as git. From that point onward, your program needs to behave as git in every possible way, and every time it doesn’t, you have a bug. Over the years, hub had more than plenty of these.

Let’s say that you want to implement a git clone <owner>/<repo> command and have it auto-expand the URL of a repository. Here are some considerations your program would have to make, right off the top of my head:

- To isolate the

<owner>/<repo>argument, you need to parse command-line flags exactly how coregit clonedoes. Whenever you think you have reached parity, a new version of git that adds new flags may come out and you might be forced to compensate. - Core

git clonealso supports cloning local directories. If the<owner>/<repo>portion also happens to match a directory that happens to exist locally, should it expand to a URL or stay unchanged? - Before you can scan the filesystem to solve cases such as in the previous item, you need to first parse, respect, and forward to nested

gitinvocations all global flags such asgit -C <dir> --work-tree=<path> clone .... - When you expand the repo clone URL, should you use the

https:,git:,ssh:or other protocols? How do you make the right decision as default, and how to you let the user choose their preference? - What if the user doesn’t intend to clone this repo from github.com, but from their GitHub Enterprise instance on another host? You now need to support selecting the hostname and maintaining different modes of Enterprise authentication.

- If you want to support SSH clone URLs, you now also need to parse and respect hostname aliases from the user’s

~/.ssh/configfile. - When you expand a git command with new functionality/flags, how are you going to add that information to

git clone -h? Remember that there are alsoman git-clone, andgit help clone [--web]. - When you add new flags to a git command, how are you going to make sure that the additions appear in git completions for bash, zsh, fish, and possibly other shells?

In hub, we’ve made decisions and workarounds for every of the above points and many more, but they always fell short. There was always something that we missed; some edge case that we haven’t considered. For example, the brittlest of all hub features are its extensions to core git completions that inject extra commands and flags into different shells. This never worked perfectly in the first place, kept falling out of date, and frequently breaks with newer releases of git. In the end, maintaining something like this is a Sisyphean task.

Instead on focusing on git extensions, over the course of the last couple of years I gently steered the direction of the project to act more as a command-line API client with a focus on functionality that facilitates scripting. By shipping such features I was able to close dozens of feature requests for hub with an explanation that users are now able to script their workflows without hub necessarily implementing them. It worked wonderfully.

If I was redesigning hub today, I would make an entirely different set of decisions.

First of all, I wouldn’t even consider making a git proxy anymore. I love git, but my time is better spent doing things other than carefully reimplementing parts of core git functionality. Git already has a plethora of functionality and instead of extending it, I now understand that the way to improve git is to design better abstractions around it. Of course, the latter is much harder work, since every abstraction will inevitably fail to encapsulate someone’s particular flow. This effect could potentially be mitigated by better defining and understanding who the audience of your product is.

Second, I would focus on strictly maintaining a command-line scripting core that does little more than offer GitHub API authentication, encoding, and logic that maps git remotes to GitHub repositories. All auxiliary features—such as custom commands—would be built on top of this core. Furthermore, anyone could roll their own commands; users wouldn’t need rely on the mainline to cover their use-cases as much and there would be less technical debt over time.

Third, instead of feeding my own personal Not Invented Here syndrome, I would opt to use more community-supported libraries and tools to avoid maintaining too many custom approaches of my own. Every component that an open source project implements in an unusual way is a potential barrier to contribution, and I have a feeling that hub is difficult to contribute to since many people offer to make a fix or implement a feature, but very few actually follow up with a pull request.

Luckily, I am given a chance to make an entirely different set of decisions: for the first time in 10 years, GitHub is investing in having an official “GitHub CLI” product of their own and they hired me to work on the project as my day job. My new team is largely people who make the awesome GitHub Desktop and together we sat down and made a decision early on to start a new product from scratch rather than building on the rickety foundation of the hub codebase.

The GitHub CLI that we are building is not exactly what I would have chosen to create if I was the only person in charge of making it, but this is A Good Thing. Before, I never really made an effort to understand who the audience of hub was, but with an actual team we finally get to explore that and hopefully build something that’s ambitious not in terms of the number of features it offers or how much of the GitHub API it covers, but in how well it helps people be productive with their daily work.

What does this mean for the future of hub? Since I personally don’t find it valuable to spend my time maintaining two separate command-line clients for GitHub, I will gradually reduce my involvement with hub to a point where it either goes into complete feature-freeze mode or finds new maintainership. It’s still too early for me to tell how exactly any of this is going to play out, but rest assured that hub is going to continue to exist and receive bug fixes until further notice. I still use hub every day and I have no intention of disappointing any people who do the same.

If you have any further questions or ideas about GitHub features that you would you like to see on the command line, please reach out to me. Thank you for reading! 🙇♂️